There has been an avalanche of tier lists in the last few years. I constantly see lists ranking everything from the best cup of coffee to the most significant philosophers – which that’s not a weird thing to rank. It’s pretty much the same as sports! I’m looking forward to the Ancient Greek Thought League finals (boo, Plato)!

On the surface, these lists seem like a lighthearted way to navigate our over-saturated world of choices, and for the most part, I don’t think people think much about it. People obviously don’t log in to TierMaker.com with the intent to erode society, but beneath lies a more complex and, I think, insidious phenomenon.

Philosophy, literature, visual art, and people (which I see many tier lists of, as well) resist simplistic categorization. Of course, these things are not like sports; specific rules and objective outcomes do not govern them. Conversations around them are highly subjective; debate, interpretation, and the evolution of ideas are parts of what makes life interesting.

Turning the profound into the easily rankable not only strips these disciplines and individuals of their depth but also molds our perceptions and interactions. So what do we lose in this relentless pursuit of ranking and categorizing? And more importantly, who benefits from this reductionist view of our world?

Consumer Culture and Psychological Implications

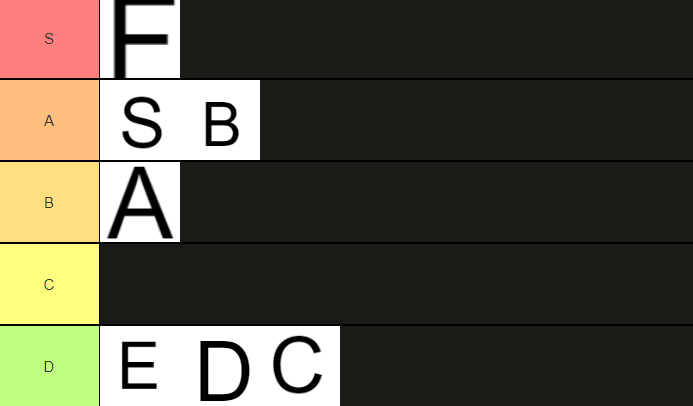

The “tier list mentality” assesses the perceived value of recommendations in a relative, hierarchized manner (rather than a specific critical examination of any one work). When one is ranking Oppenheimer or Barbie (both of which I was critical of, Oppenheimer moreso) in a list of 10 big movies from 2023, the discussion becomes less about what the film represents or attempts to say and more about which movie people would rather watch relative to other named films. That is, it becomes about choice in a consumer market.

Tier lists, by their very nature, encourage a comparative approach to viewing cultural products and experiences. They not only rank items in a hierarchy (which creates an illusion of an objective relative value measurement) but also implicitly invite users to compare their preferences. This feeds into an increasingly competitive culture, where individuals vie for validation by expressing unique or popular opinions.

It promotes engagement that is less about appreciation or understanding and more about distinguishing oneself through alignment or opposition to the prevailing rankings. Users often engage in debates or discussions not to understand differing perspectives but to assert the superiority of their own. This behavior aligns with the broader social trend, fostering environments where comparison and competition are central to interactions.

On social media, tier lists are not limited to cultural products or experiences; they increasingly encompass the ranking of individuals (like influencers or even mutual followers), transforming social relationships and personal qualities into quantifiable and rankable data. Here, we see a more insidious result: reducing human beings to mere objects of appraisal and entertainment. This aligns with the broader commodification of all aspects of life, including human relationships and identities, present in capitalism in its imperial stage.

The psychological impact of this trend is profound. It fosters an environment where self-worth and social standing are constantly measured and judged against arbitrary and superficial criteria. It is not purely due to tier lists, but they contribute to a mode that has increased social anxiety, a sense of inadequacy, and a distorted view of oneself and others.

Furthermore, the ranking of individuals on tier lists contributes to a marketized (or gamified) view of social interactions, where people are valued not for their qualities or skills but for their perceived rank on a socially constructed scale. This undermines the capacity for empathy and to respect others’ humanity and dignity.

TierMaker.com (a Tastier Adventures brand) seems to monopolize the practice, with every tier list I see using its distinctive template. Their site is easy to use, at least for making tiers. If one wants to find out who owns TierMaker, it is not.

The simple answer is, of course, “Tastier Adventures.” However, I spent some time trying to find out who Tastier Adventures is by going through the four brand sites they list, and they do not have any contact information outside of gmails for each. The whois information is private, as well. The only link to the outside world I could find was on their Facebook page, where the sole like/follow is “SteveTAGamer.” I can’t say with any certainty this YouTuber is involved in TierMaker; however, he does make TierLists.

Regardless of who owns it, TierMaker is a tool to facilitate these effects on culture. This doesn’t make it “bad,” as some will assume I intend to claim. However, it would have been useful to know who owns it to help us distinguish whether it is a product of incentive or vertical integration…

Vertical Integration and Finance Capital

Tier lists are also part of vertical integration within media conglomerates. I recently put out a simple video on vertical integration, and the response indicates to me it needs to be talked about more. Vertical integration is a business strategy where a single company controls multiple stages of its production process that separate companies would otherwise operate.

When a media outlet owned by a larger business entity also holds stakes in other content production companies, a conflict of interest arises. Tier lists can quickly become a promotional tool, favoring the conglomerate’s own content, products, and interests.

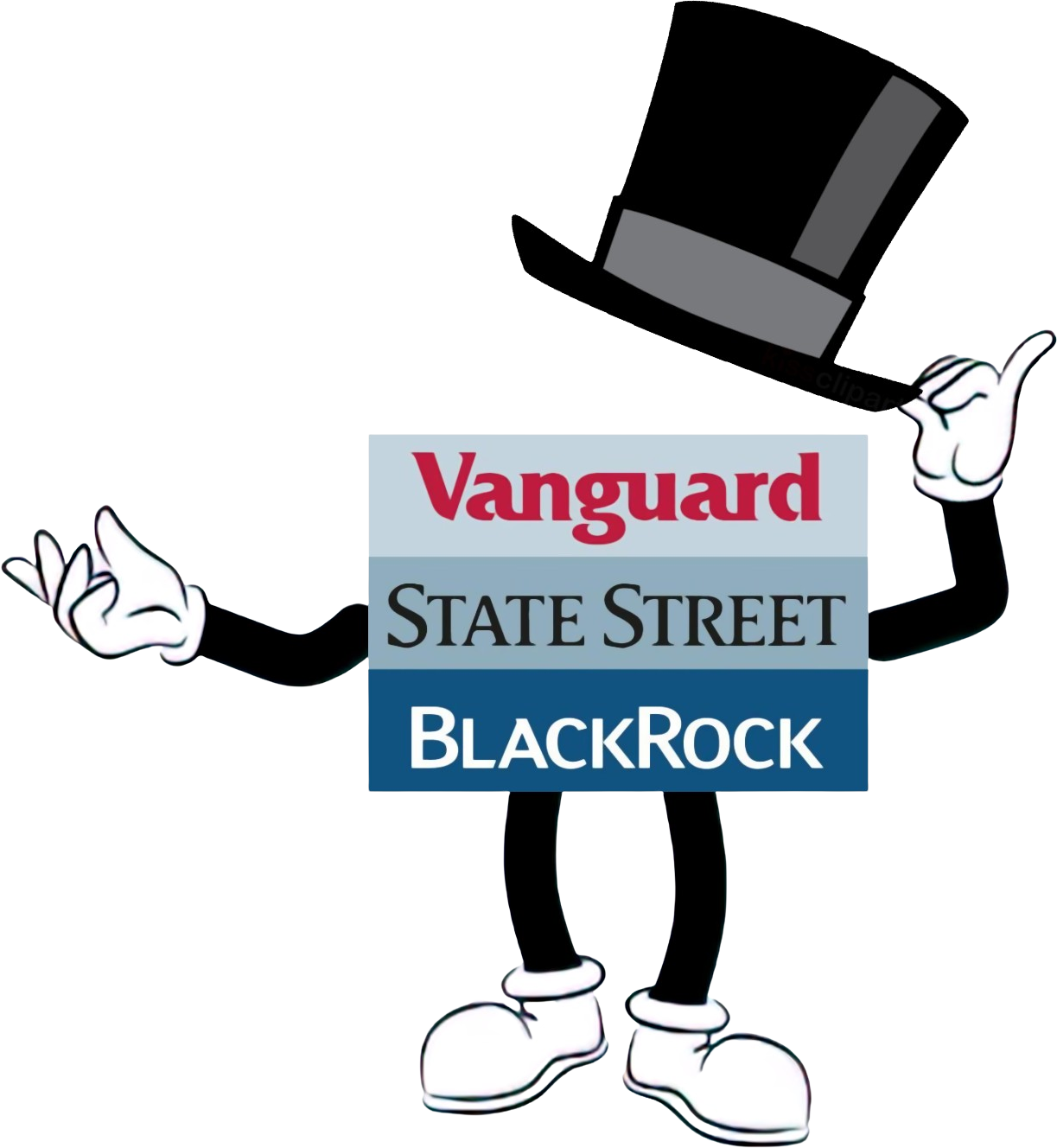

Further, the influence of investment giants like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street cannot be ignored. These firms hold significant stakes across a spectrum of industries, including both media outlets and content creators. This interconnectedness raises questions about the impartiality of tier lists. Are these rankings truly reflective of quality and popularity, or are they influenced by an intricate web of corporate investments and benefits?

These companies own large stakes in Disney, Comcast, and Paramount, major entertainment content creation and distribution companies. They also own significant stakes in The New York Times, News Corporation (owners of The Wall Street Journal, among others), Vox Media, and BuzzFeed. Thus, while these are separate companies, it could be argued this is a broader form of vertical integration due to them ultimately being under the same umbrella(s).

These conglomerates see art, entertainment, and even personal preferences as commodities. This commodification serves a dual purpose: it standardizes cultural products for profit and promotes a consumerist ideology. By ranking cultural items and experiences, tier lists subtly encourage passive consumption as the primary mode of engagement, aligning perfectly with capitalist interests and prioritizing market transactions over artistic or cultural value. Energy is directed into advocacy for one’s passive consumption.

Furthermore, the role of these conglomerates in cultural dissemination is a cultural manifestation of imperialism. Dominant capitalist powers exert influence and homogenize culture globally through finance capital, and I think it’d be absurd not to include these dynamics under that critique.

This isn’t to say “tier lists are automatically imperialism,” but we should understand that they can manifest corporate interests and promote a narrow range of cultural products, reflecting the preferences and values of dominant capitalist entities. It should not be a stretch to imagine the mode that has propagated them so prominently has a reason to.

Simplification and Propagation

Tier lists represent more than a mere ranking system; they help manifest a culture prioritizing consumption and comparison. In their simplicity, these lists often strip complex subjects of their nuances, reducing them to an easily digestible format. This is not just a matter of convenience; it reflects and reinforces a passive consumption mentality, influencing people’s choices and preferences toward what is more popular or heavily promoted.

In various online communities, about everything from music to personality types, there’s a growing number of people expressing fatigue over the repetitive nature of tier lists and frustration with their lack of depth. The thing I see most complaints about is their tendency to oversimplify complex subjects.

For instance, when music, a form of art that resonates with deep emotional and cultural layers, is reduced to a tier list, many worry it removes focus from the experiences and feelings they represent. Rather than understanding and discussing aspects of the art, people feel railroaded into simply consuming it and asserting it is “good/bad” and “better/worse than that other thing.”

Similarly, when ranking personality types or people, tier lists promote a viewpoint that sees individuals and their complex traits as items to be assessed and placed in a hierarchy. This not only diminishes the richness of human diversity but also fosters a mindset where people are viewed through the lens of comparison and competition rather than understanding and empathy.

The repetitive nature of tier lists also contributes to a certain monotony in public discourse. They encourage a herd mentality where opinions and tastes are influenced more by what is deemed popular in these lists rather than exploration and discovery. This can lead to a homogenization of preferences and opinions, where the mainstream and marketable overshadow the unique and unconventional.

It not only reinforces a mode of consumer choice in all aspects of life, it also canonizes certain entirely subjective choices as “better.” Without dictating one must make a specific choice, it creates stigmas around “less popular” choices by conflating them with an objective-looking hierarchy. Thus, an ideology that manages and reproduces subjects’ behaviors is created.

Conclusion

These lists are more than just a benign ranking system. They reflect a more profound societal shift towards a market-driven, commodified way of viewing the world around us.

We're not just ranking movies, music, or even people; we're being fed a worldview where everything, including human experiences and relationships, can be quantified and consumed. This reductionist approach strips away the richness of the human experience and the depth of our individual and collective narratives.

Remember, our world is far too intricate and colorful to be confined to tiers. We are all capable of engaging with the world in all its complexity and beauty. But it isn’t our fault when we don’t.

This is another means of control built into the house rules.