Oppenheimer (2023) is Tedious Imperial Propaganda

How the feelings and opinions of a man racked with guilt draw us away from the real story.

In Oppenheimer, the titular character attends a communist dinner gathering, where he claims to have read “all three volumes” of Marx's Das Kapital. In justifying why he won’t join the Communist Party, he summarizes ideas as "ownership is theft." A party member corrects him, saying it’s “property is theft.”

Oppie, as he is later fondly referred to by his underlings, retorts: “Well, I did read the original German version.”

And yes, “property is theft” is the correct translation of the original German writing…. of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, an anarchist Karl Marx was heavily critical of. Marx decried Proudhon’s 1840 book What is Property? (where “property is theft” originates) saying, “The deficiency of the book is indicated by its very title.”

Karl Marx went beyond simply dismissing his idea that “property is theft” as bourgeois-justifying; he roundly described Proudhon’s work as “bad, and very bad at that.”

Oppenheimer has garnered much praise for its supposed “accuracy,” which I assume is what people must tell themselves to enjoy this tedious supposed “magnum opus” from Christopher Nolan. If this egregious, naive, Breadtube-level read on Marx is any indication, then accuracy is not a reason to see it.

So, taking accuracy off the table, are there other reasons I’d say Oppenheimer is worth its 3-hour runtime? Absolutely not. Ultimately, it’s just more pro-imperial capitalist propaganda.

“Theory will only take you so far”

Christopher Nolan enjoys non-linear storytelling. In an interview, he said he uses non-linear structures in his films because he doesn’t like that “television has imposed” more “simple, linear” expectations on storytelling.

Theoretically, a film about an obviously sequential series of historical events doesn’t need to be linear. However, as Oppenheimer famously said (or rather… didn’t; I took accuracy off the table for a reason), “Theory will only take you so far.”

Nolan opted to jump around this story’s timeline as much as humanly possible. Further, as if to say, “I am as subtle as I am linear,” Nolan also portrays Oppenheimer’s primary detractor’s perspective as literally black-and-white, not comprehending the nuance of Oppie’s complicated worldview.

The fantastic visuals inside Oppie’s head during our introduction to the story almost acknowledge that Nolan has no idea how to do the exposition for this one, clawing for some way to bring the viewer in. Oddly enough, those visuals were significantly more interesting than the much-vaunted-but-underwhelming nuclear explosion.

I have plenty of criticism for Barbie, this summer's more feel-good capitalist propaganda piece. Still, I at least enjoyed some of its humor (Ken’s enthusiasm for the patriarchy and the song “Push,” specifically). While I think the performances in Oppenheimer are legitimately superb, it was hard to find the film enjoyable.

Speaking of Barbie, one thing it can be credited for is writing women as characters with actual traits and story arcs (though it was pretty obligated to, given “progressive” subject matter). Oppenheimer’s women are accessories at best. This isn’t to argue that “representation matters,” and women’s role in society was much more restrictive, given the setting.

Still, neither point necessitates portraying women as minimally and two-dimensionally the way this film does – often only as Oppie’s playthings and nothing more (ironic that between Barbie and Oppenheimer, the latter is the one that treats women more like toys). The one (brief) time a woman gets to be a legitimately intelligent person in the film is during his defense.

Imperial-Stage Capitalist Propaganda

I saw this film on recommendation from my mother, who thought it was “full of information.” She assumed that would be something I would like because I often say things that are also “full of information.” This is not an insult coming from her; to be clear, she thought the film was outstanding and is supportive of my work. However, that she would characterize something as “full of information” as an automatic asset can help the reader understand my critique of the film.

“Information” is a neutral word. Oppenheimer is not a neutral film.

I called her up after seeing the film and said, “This film is ultimately pro-imperial propaganda.” She responded, “but he’s so regretful! He clearly views the bomb as a bad thing.”

So, in addition to the comment I said to my mom, I’d like to add that it’s effective pro-imperial propaganda.

This film is not about the bomb, the US’s state’s genocidal actions, or about why the power to assemble and use such a thing exists; it’s about J. Robert Oppenheimer. Thus, it is about the ideals and thoughts of an individual. I’m not going to articulate an obvious “Great Man Theory is bullshit” criticism, but if this were an anti-war, anti-imperialist film, J. Robert’s life, thoughts, and opinions don’t fuckin’ matter. Hiroshima and Nagasaki are genocidal war crimes.

Of course the man who drove the creation of a device that killed between 110,000 and 210,000 city-dwelling civilian people in Japan will feel guilty. No human being wouldn’t. To direct our empathy toward the regretful man who spearheaded the creation of the bomb is sleight-of-hand, intentionally or not. Over 100k people died, and while we saw Oppie briefly imagine his people caught in a nuclear explosion, we saw nothing of the damage done. It is mentioned casually, and our titular scientist is basically called a pussy to his face for caring.

The question of Oppenheimer’s recognition of wrongdoing is the audience’s main problem to deal with emotionally, and the fact he feels guilt is the release from that tension. The heads of state say things like “I worry about America when we do these things and no one protests.” So, Oppenheimer knows it was wrong to nuke Japan, the US leadership knows it, and so do we. Why say anything else?

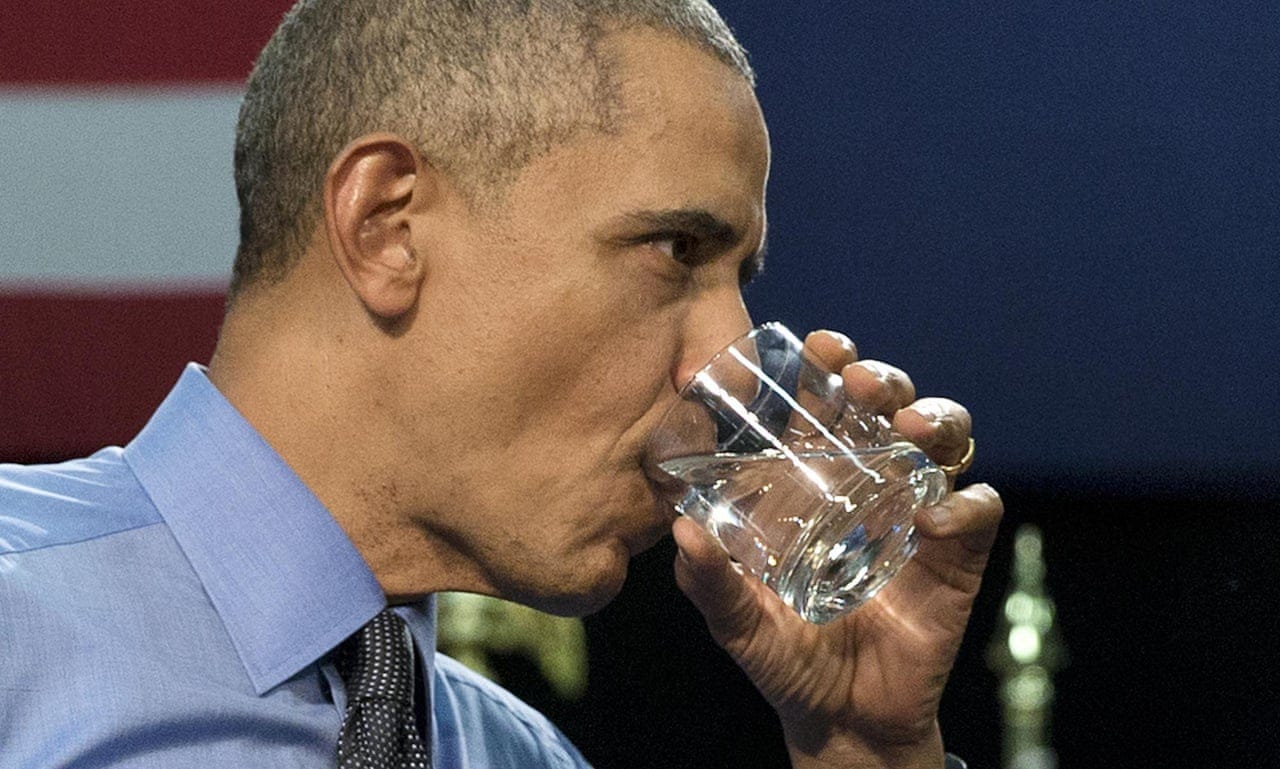

When President Barack Obama visited Flint, MI in 2016, the water had been undrinkable due to lead contamination for years. The city’s residents were excited at the idea he was acknowledging it, that the US government’s significant resources would be directed towards them – as had been promised months before. Instead, he said, “I see you, and I hear you,” and asked for a glass of water like a total psycho.

Most work done to replace lead pipes in Flint, MI occurred after Obama was no longer in office. Oppenheimer is the equivalent of his 2016 press conference – it tells us “We see you, we hear you,” but it either doesn’t want us to understand, or it’s simply that Nolan himself doesn’t.

This film treats the bombing of Japan as a necessary evil, and we are to understand that it is bad, but we are not to think about it beyond that. Perhaps more people wouldn’t have found this detached position adequate if the true horrors had been depicted. I don’t know, but this film spends its time morally appeasing people’s guilt.

Well, you know what? I feel no guilt for Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I had nothing to do with them, and neither did the reader, regardless of generation. We do not have the ability to direct the US military, allocate funding to weapons programs, or give the order to drop a bomb. Further, we have no reason beyond mere curiosity to interrogate the morality of a man who, to be frank, did not bomb Japan. There’s no question to ask here; I am happy to accept that he felt everything he said he did in the film. I am happy not to regard him as a monster.

The fact is, those deaths are the result of an imperial-stage capitalist state, one that exists to this very day. If we are emotionally satisfied by depictions of hearings in tiny rooms about whether or not a man feels sufficiently bad about the horrors of nuclear war – and if he was loyal to the US state(!) – then why would we pick at such an old wound? Why would we further interrogate something we have experienced catharsis for our moral correctness?

Part of the narrative we’re supposed to understand is that J. Robert Oppenheimer lobbied as hard as he could for international cooperation to avert nuclear proliferation and a nuclear arms race. And we were repeatedly told it was futile, out of his hands. He was merely a scientist, not to involve himself in political matters or he would get slapped down.

It has been widely publicized that Christopher Nolan wrote Oppenheimer’s screenplay in the first person to embody his perspective. Arguably, if Oppenheimer felt guilty but was also loyal to the US state – which he had no power over despite his status – this is how we’re also supposed to feel.

Further, he was left-wing but not a communist! I very much agree with dichotomizing “left” (as well as “right”) from “communist,” but the point here is “you can be left and dissident, but you should also default to US foreign policy, unlike those filthy anti-imperialist commies.”

Media Literacy

Oppenheimer is emblematic of a balancing act that Nolan is beholden to: he wants to make a film that people are interested in and feel something from watching. However, it is also about historical events that bear so much weight that, frankly, it renders character study superfluous. It seems the film wants to examine nuclear warfare critically. However, by hyper-focusing on its titular character as a tragic hero who wrestles with guilt, it avoids what ultimately needs to be addressed: imperialism.

Nolan's presentation of Oppenheimer, an individual laden with regret, can be seen as an attempt to embody the lessons of war in a human story. While this might be seen as an artistic approach, it totally fails. This is history, not entertainment, and thus should deal with the larger, interconnected implications. But too many big, important things felt like they flew by in the periphery, while little moments were center stage.

Regarding narrative, one might say, “That is how a filmmaker should treat character study,” which is arguably correct. However, the information I learned in high school history class about the bombing of Japan also tugs at these moments – is it not more important than whatever Einstein said to Oppenheimer? Robert Downy Jr.’s brilliantly-acted Lewis Strauss is chided for making that moment about himself, that maybe they were talking about something more important than him.

But they weren’t. They were talking about themselves and their legacies relative to their creations. Also, did that conversation by the pond even happen in reality? Probably not; it’s provided for narrative reasons. If it did, was it anything like what was portrayed? Probably not. We weren’t there, and the two men who were had no reason to divulge this conversation to anyone.

I could not shake an uncomfortable feeling as I watched: I was both bored and irritated that I was bored due to the gravity of the situation. Is my attention span the issue? Should I not be able to sit through what is ultimately essential history?

In retrospect, I see this boredom as irritation with the aforementioned hyper-focus on what our designated “important people” felt about this essential history.

In focusing so heavily on Oppenheimer's internal conflict, any potential for what I see as a more vital criticism of the broader systems of power was sidelined. The ability of a state to have taken hold of the resources to create and drop an atomic bomb is taken for granted; it just is.

Oppenheimer is, however, a narrative film. The medium in which this information is presented prioritizes character arcs, visual spectacle, and evocative musical scores. The very nature of cinema might mean that individual stories, like Oppenheimer's, take precedence over broader systemic critiques, leading to a more personalized and potentially less critical narrative.

A documentary film or a book could better serve this – perhaps even the book this film was based on, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. I have not read it, so I can hardly say. Still, if I were given the opportunity to present this information on a massive platform, it would not be in a way that fundamentally requires us to think about ideals and feelings rather than global implications (and no, ideas aren’t the foundation for change in the material world).

And therein lies the real tension: this is the only form in which capital would allow someone to tell a story that ultimately damns the mode of production in its imperial stage. If they are going to fund such a story, it’s going to be the version that hyper-focuses on ideals and feelings. Nolan doesn’t have to be writing propaganda; he has to write what he sees as an entertaining version of a book he was given the greenlight to adapt.

Those who gave this greenlight know what to expect from him in quality, scope, and focus.

Conclusion

Oppenheimer exemplifies adaptive cinema's delicate line between historical accuracy and entertainment. While the film contains bursts of brilliance in terms of acting and visual prowess (though not where I expected it to be), it narrowly focuses on the internal struggles of its titular scientist, sidelining the profound, broader implications of the events. The narrative basically ignores the global implications and the stark consequences of imperial-stage capitalism by exclusively shining the spotlight on Oppenheimer's personal guilt and self-reflection.

This is also unavoidable; the very essence of narrative film often prioritizes individual stories and emotional arcs, which is hardly conducive to systemic critique. This isn't just about Nolan's artistic choices but reflects a broader issue with how our culture digests history; the choice to zero in on an individual's moral plight, rather than the devastating impacts of the imperial state, is reminiscent of “historical amnesia,” where audience's emotions are pacified and redirected. Instead of grappling with the grave implications of the atomic bombings, we're swayed into a discourse of personal guilt and redemption.

I certainly am not going to criticize people who enjoy this film. There are things to like about it, and if Nolan’s reliance (I would say over-reliance) on non-linearity appeals to you, it might be a good way to learn about J. Robert Oppenheimer’s perspective.

But that’s all it is, and I can’t help but think it’s not enough.