I've always thought people yelling about how “fan artists are real artists” is bullshit. In fact, I have previously looked down on “fan art.” Sure, I have thought, “There is some good fan art out there,” but overall, I saw it as a subordinate type of art, a lesser form.

But recently, I have been spending a lot of time talking about intellectual property law and what it means to be creative. I have released several videos about it (including “PALWORLD: Plagiarized Pokémon?” and my latest, “Wookieepeditis”) and have been working on a documentary that examines this through the lens of Platonic elitism. Somewhere along the way, I realized this framing is unfair and delegitimizing these people and their work.

They are not “fan artists;” they are artists. The framing subordinates them to the mechanics of intellectual property, in which the only way they aren't “plagiarists” is if they aren’t “real artists” in a certain way.

I have completely rethought this; they are just straightforwardly legitimate artists, and I do not believe they deserve the word “fan” foisted upon their work.

Why “Fan Art” is Dismissed

To understand why “fan art” is often sidelined, we need to examine the deeply ingrained notions of originality and authenticity in our cultural ethos. Mainstream appreciation of art frequently hinges on the idea of the “original” – a work that springs forth from the unique vision of an individual artist, untainted by external influences. “Fan art,” by this definition, is seen as derivative, a secondary response to a primary source. This skewed perception overlooks the fact that all art is, in essence, a dialogue – a continuous conversation between the artist, their influences, and the world around them.

The creativity and skill involved in “fan art” are not automatically profound and world-changing – but then again, nor is it in “original” work. Often, world-building in “fan fiction” not only engages with the established universe but offers new depth. These extensions can explore untold backstories, delve into “what if” scenarios, or even (my favorite) critique the original work’s themes and ideologies. This is not a simple mimicry; it’s a creative process that requires an understanding of the source material, coupled with the ability to articulate one’s own experience through it.

However, the dismissal of fan art is not just a matter of perception; it is intricately linked to the broader phenomenon of fandom as a marketing scheme. Fandom, in its current form, is often a cultivated identity – a concept I explored in my 2018 book, Custom Reality and You. It's a tool used by the ruling class and capitalist structures to shape and manipulate personal identities for profit and/or control. By placing a commodity at the center of one’s identity and community, fandom transforms genuine engagement into a vehicle for consumerism.

“Fan art” is often seen as an extension of the commodity rather than a legitimate artistic endeavor. The ruling class benefits from this perception, focusing on their officially sanctioned, profit-generating content while sidelining community-driven, creative expressions that emerge organically when the intellectual property causes dialogue in everyday life.

Intellectual Property

The classification of “fan art” and “fan fiction” is not just a benign categorization but a form of subordination that denigrates these creative expressions. This classification system underpins a hierarchy of “legitimacy” that places undue emphasis on “original” creations while undervaluing “derivative” works (because, again, all art is derivative).

At the heart of this is how intellectual property laws have shaped our understanding of what constitutes “legitimate” art to accommodate bourgeois property relations.

Under this framework, the value of a piece of art is often measured by its “originality,” which is ultimately about who really owns it. This automatically places fan-created works at a lower rung simply because they draw inspiration from existing content. This perspective fails to recognize that creativity is not a finite resource exclusive to “original” works but is abundant and manifests in many forms.

This skewed valuation is evident in the practices of corporations like Disney, which famously built an empire largely by adapting stories from the public domain - classic tales that belong to our collective cultural heritage. Yet, seemingly paradoxically, the same company has been a prominent advocate for copyright protections. This contradiction highlights the inherent flaw in the current system: it venerates the idea of originality in one breath while capitalizing on shared cultural narratives in another.

Furthermore, Disney's approach to public domain stories is a prime example of how the notion of “original creation” is a misnomer. These stories, although reinterpreted and presented in new forms by Disney, are not new in their essence. In fact, all of the beloved “adaptions” Disney has given us are, in many ways, “fan fiction.” Yet, under intellectual property law, these adaptations are given the same status and protection as any other “original” works, thereby perpetuating a cycle where adaptation is only valued when it serves corporate interests.

This situation leads us to question the very foundations of our current intellectual property laws. Today, a corporation can claim ownership and exclusive rights over stories that have existed for centuries, and fan art, which also draws from and expands upon existing narratives, is often subordinated and afforded no legitimacy.

Reevaluating “Fan Artist” as a Title

I believe it is crucial to challenge the terms “fan fiction” and “fan artist.” These creators deserve recognition not as mere appendages to existing works but as artists in their own right. The very idea of “fan art” as a genre allows people to dislike “fan art,” dismissing it outright rather than considering what it might say. When one says “fan fiction mostly sucks,” one is holding fan fiction to a different standard than all fiction, which also mostly sucks. “Fan” work is not different in this respect.

The implication is that such creators are merely fans first and artists second – consumers rather than creators. It suggests that their work, no matter how creative or skillful, is secondary. This is the germ of a bias, subtly enforcing the notion that being inspired by existing works diminishes art’s value, but again, all art is derivative. This categorization not only unfairly demeans the work of these creators but also perpetuates a narrow and exclusionary definition of what constitutes art.

All artists, in some way, are inspired by and respond to the works of others. Artistic creation has always been a cumulative process, building upon the ideas and expressions of those who came before. To label one form of this creative process as less valid or legitimate than another is to misunderstand the very nature of artistic expression.

People wonder why I keep bringing up public figures like Hbomberguy and their critiques of what is “original” and their stoking of plagiarism controversies. Here, I am pointing out that they are at odds with a significant portion of their own supporters, which often includes not only “fan artists” but a lot of anti-capitalists and/or anti-establishment types. By advocating for a strict interpretation of originality, Hbomb et al. align themselves with a view that devalues the contributions of fan creators from a stance of reinforcement of bourgeois property relations.

Ultimately, concerns about “originality” are about ownership, not creativity. Hbomb, here, is staunchly advocating for capitalism and bourgeois class rule.

The release of Palworld, a game that has been both criticized for its derivative nature and lauded for its engaging content, has highlighted a significant shift in the conversation. Despite accusations of being unoriginal or even plagiaristic, Palworld shattered sales records and garnered overwhelmingly positive reviews. This response underscores a growing sentiment: many people value the enjoyment they get from the combinations of derivative ideas this game offers.

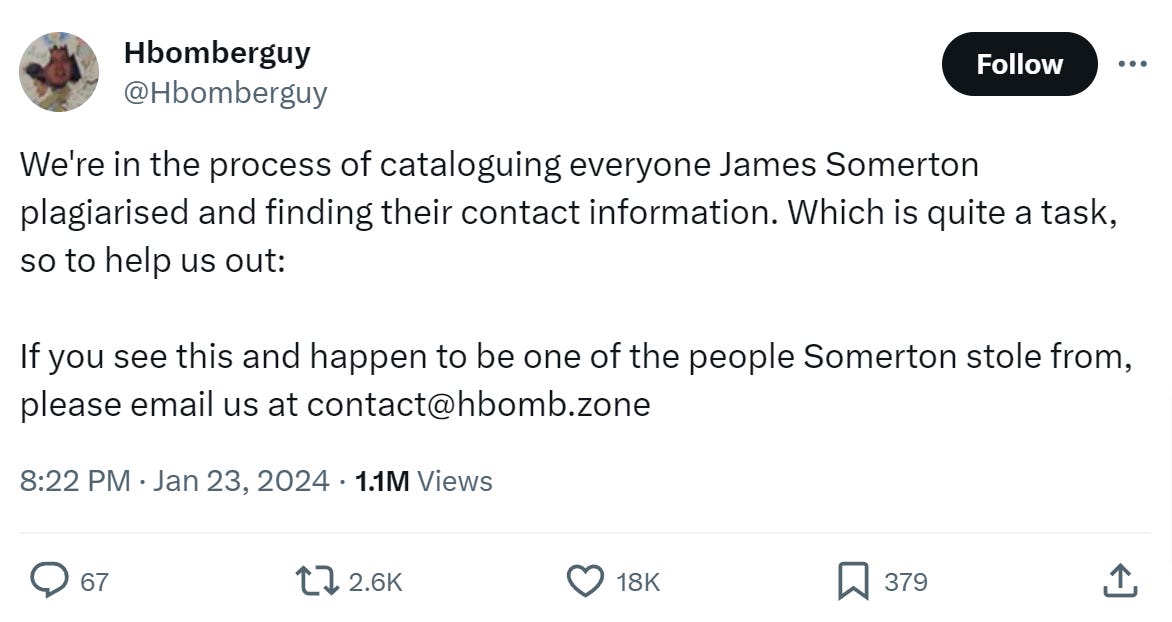

In an interesting turn of events, shortly after Palworld's successful launch, Hbomberguy redirected attention to James Somerton through social media. This move, soliciting a list of those allegedly harmed by Somerton almost two months after the initial controversy, appears to be an attempt to regain some narrative control.

I talk about him because these controversies surrounding originality and plagiarism are not merely debates about artistic integrity; they are deeply entwined with enforcing bourgeois property relations. These discussions are framed around protecting the sanctity of “original” art/artists but serve to uphold a system of class rule.

We are, in effect, participating in a larger discussion about who is allowed to create, inspire, and be inspired.

Conclusion

The discussions that frame “fan art” and “fan fiction” as a lesser form of creativity and the controversies surrounding originality and plagiarism are related – and they’re not just about artistic integrity. They are, more profoundly, about reinforcing a system that prioritizes ownership and commodification over a communal, iterative nature of creativity.

Public figures who advocate for a stringent interpretation of originality support this capitalist framework, whether that is their intent or not. They ultimately find themselves in opposition to the ideals they professed on their way up. By equating originality with ownership, these figures reinforce a perspective that devalues the contributions of creators who draw inspiration from existing works.

This perspective is detrimental not only to “fan artists” but to all artists – as well as anyone who enjoys any form of art. It stifles the freedom to create, to be inspired, and to inspire others. It overlooks the fact that art, in all its forms, is a dialogue — a continuous, evolving conversation that enriches our cultural and social landscape.

I know I'm late, but I just remembered this and it just hit me why this article felt so off to me:

Peter, have you ever been in a fandom? Like, an actual, honest-to-god, has-a-presence-at-a-comic-or-anime-convention, fandom?

Most of us don't really see "fan art" or "fan fiction" as pejorative labels, we use them as a simple factual descriptor. I made this thing as a fan of the subject matter. That's it. None of us see ourselves as prostrating to some corporate behemoth; hell, if you actually scope around fandoms, you'll see just as many people criticizing the corporations or creators behind our favorite works as you'd see people uncritically praising them, and every viewpoint in between. I've been involved in many a fandom where we loved the story and/or characters DESPITE the people who own the rights; for God's sake, I was in the Overwatch fandom, mocking Blizzard was practically a pastime for us.

Anyway, I also feel the term "fan fiction" especially deserves to exist because it's a bit of a different medium than more traditional literature. Not just in terms of it mainly existing online or in zines, but also because the expectations are different. Worldbuilding isn't as essential, serialization is way more common, and there's even tropes pretty much exclusive to the medium. Then again, I'm not sure you're even aware of said tropes, you don't seem like the kind of person who would know the terms "Omegaverse" or "Coffee Shop AU" off the top of your head.

Point is, this bugs me because it feels like it was written by someone who's not actually that familiar with the subject matter. Every time you mention "fandom", it feels like we're talking about something different. You say "fandom" to mean a base of uncritical consumers, I say "fandom" to mean a group of different people brought together by a common interest. Yeah, there's shitheads in fandoms, but you could say that about any community.

Maybe I'm just defensive because of the fact that fandom's played a big role in my life. I learned new art skills from drawing fan art of particular shows. I met lifelong friends and even my longterm partner from fandoms related to YouTubers. And yes, I learned some harsh lessons about who not to trust from fandoms I was in as a naive teenager. But regardless of my bias, I just wanted to get this off my chest.