"The Mandela Effect"

Useful term or thought-terminating cliché that obscures creative labor?

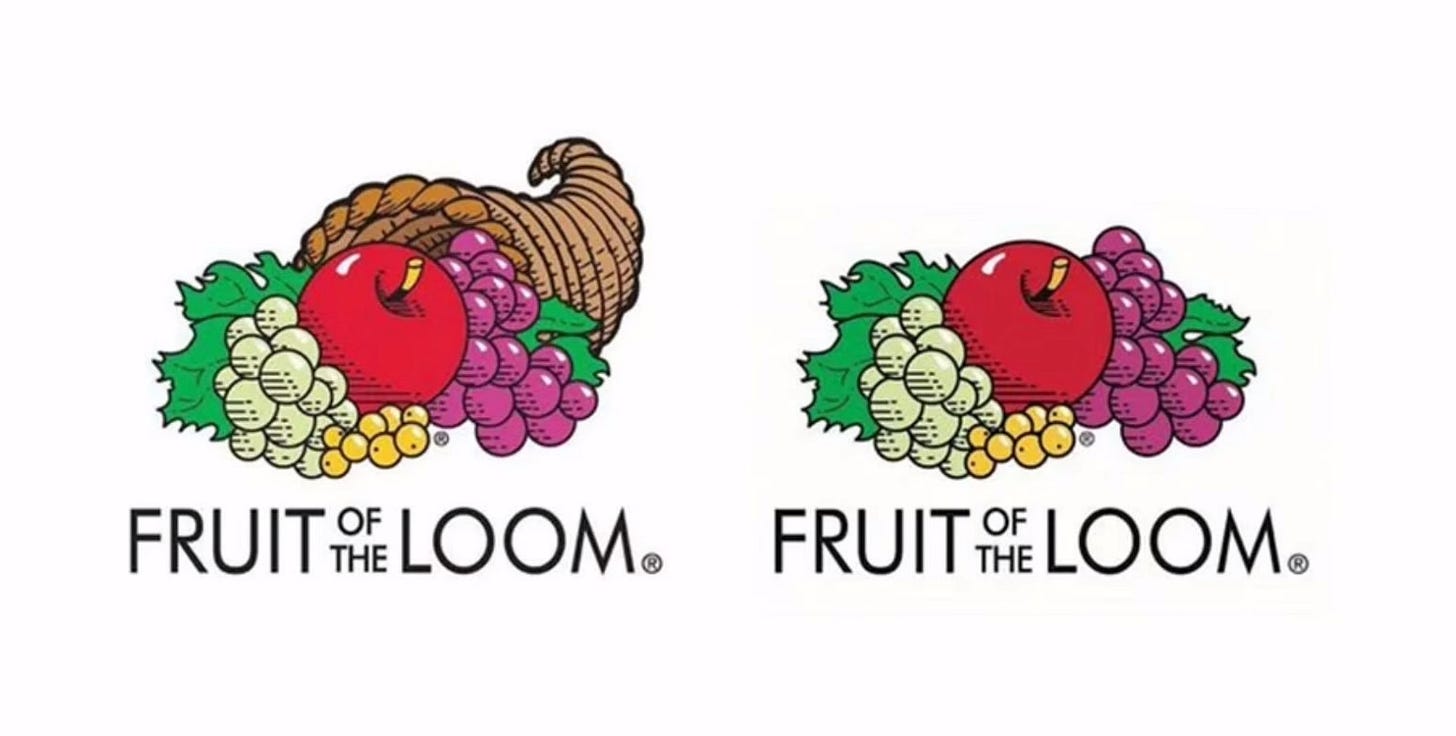

The Mandela Effect, a term that has gained traction in both pop culture and psychological discussions, refers to the phenomenon where a significant number of people recall events or details differently from how they actually occurred. This concept is often exemplified by instances like the widespread belief in a cornucopia being part of the Fruit of the Loom logo — a detail that, in reality, never existed.

I made a video about this, playfully finding the answer to the question, “Is there a cornucopia in their logo?” I’d recommend giving it a watch, but there’s one thing I specifically avoided saying in the video that I have seen said in all media talking about this: the words “Mandela Effect.”

Here, I want to talk about why.

Unpacking the Mandela Effect

The Mandela Effect, a term coined by Fiona Broome, encapsulates instances where a group of people remembers something differently than how it occurred. A striking example, as I alluded to a moment ago, is the widespread belief in the existence of a cornucopia in the Fruit of the Loom logo – a detail that never existed.

Now, I have zero contention about the idea that there is such a thing as lots of people misremembering something the same way; the discussion around the non-existent movie Shazaam featuring Sinbad as a genie has gone on for years. Despite clear evidence that such a film never existed, numerous individuals vividly remember watching it, discussing it, and even recalling specific scenes. This isn't just about a few people misremembering; it's a large group.

However, before we attribute this to any mysterious cognitive phenomena, we should consider more straightforward explanations. Human memory is not a perfect record; it’s malleable and susceptible to suggestion and reinforcement. When a false memory, especially one that seems plausible or fits into existing cultural narratives, is shared publicly, it can quickly gain traction. The social aspect of memory, where we reinforce and validate each other's recollections, plays a crucial role in the spread of these collective misrememberings.

Another factor is the phenomenon of confabulation, where our minds fill in gaps in memory with fabricated details. This is not done intentionally but is rather an unconscious process of the brain trying to create a coherent narrative. This is common in situations where a memory is vague or incomplete. People like stories rather than fragments because threads get tied together. Often, as people attempt to create a whole story from pieces of information, it sometimes leads to mistakes.

Collective memory consolidation should also be considered. When we share our memories with others, especially in a group setting, there's a tendency for these memories to become exaggerated and/or homogenized. Over time, a group’s recollection can override individual memories, leading to a collective version of events that may stray from how an individual (correctly) remembers it.

Media, both traditional and social, plays a massive role in shaping our recollections. The constant stream of information, images, and narratives can create associations in our minds that weren't there before. For instance, a movie or TV show referencing a non-existent film (one that exists within its own fictional world) can plant the seeds for a collective false memory. The line between reality and fiction blurs, and our brain, striving to make sense of this influx, sometimes creates connections where none exist.

Pathologization of Common Misconceptions

I think it’s better to consider this not as a consolidated phenomenon but as a spectrum of ordinary happenings regarding human memory. To unify a “Mandela Effect,” I feel, creates and encourages a tendency to pathologize what is essentially a collection of common human experiences. By labeling these memory lapses as a distinct “effect,” we inadvertently create a thought-terminating cliché.

By having a catch-all explanation for any and all collective misremembering, further inquiry or understanding can be discouraged. A catchy and convenient label often stifles deeper exploration (and I’ve talked about empty sloganizing many times). When a complex phenomenon is boiled down to a simple phrase, it often discourages people from understanding the underlying mechanisms at play.

Additionally, it could be employed to dismiss genuine discussions or inquiries. For instance, when someone points out a widespread misconception, simply attributing it to the Mandela Effect can end the conversation, as if nothing more needs to be said. It becomes a convenient way to avoid addressing deeper issues, such as why certain false memories are more prevalent or how they reflect our cultural and psychological biases.

Attributing memory lapses to a quirky, almost mystical phenomenon can also lead to a sense of fatalism about the reliability of memory, suggesting that our recollections are so inherently flawed that they can’t be trusted. This perspective can undermine our confidence in our memory and, by extension, our sense of reality.

I think the concept of reification is relevant here. Reification is when abstract concepts or social relations become treated as concrete, tangible things. In the context of the Mandela Effect, reifying collective memory errors into a single, tangible phenomenon transforms these complex and varied occurrences into a simplistic, easily digestible concept. The concept is then commodified via repetition in tons of media and incentives to use a catchy term rather than have a deeper, nuanced discussion arise.

In this way, the Mandela Effect as a thought-terminating cliché can be seen as a symptom of broader capitalist societal tendencies. The allure of a simple, marketable concept overshadows the interplay of many factors in shaping memory.

Better Branding Through Collective Labor

But if we’re talking about reification (or commodification), we should consider the idea that it is finding a way to obscure people doing some form of labor that benefits or reinforces the larger economic structures.

Consider the Fruit of the Loom example. A “bootleg” version of the logo with a cornucopia has absolutely circulated. At this point, most people have very likely seen both versions of this logo:

In fact, this simple, unauthorized addition to a logo can be argued to have resonated more deeply with the public than the original design.

This sheds light on a key aspect of collective misrememberings: they often arise from the public’s creative engagement with branding and symbols. This unauthorized addition of a cornucopia to the logo highlights how collective memory transformation can be more than just an error — it can reflect the public’s creativity and shared cultural values.

Take another example: the Berenstain Bears. Many remember the name as “Berenstein,” with an “e.” This misremembering could stem from the commonality of “-stein” endings in names, fitting more comfortably into many people’s linguistic expectations. Many recall the famous line from Snow White as “Mirror, mirror on the wall,” whereas the actual line is “Magic mirror on the wall.” This alteration makes the phrase more rhythmic and memorable.

What these examples reveal is that these collective misrememberings can often be the result of the public’s subconscious effort to reshape branding or narratives into forms that are more meaningful or relatable – a certain collective creativity.

Folklore and public discussion are ultimately macro forms of collaborative storytelling, discussion, or even branding, creating versions of reality that, while not automatically factually accurate, are sometimes more appealing or memorable. This creative labor may not be officially recognized or authorized, but the idea it has no effect on memory and perception is laughable.

In this way, collective misrememberings can be seen not just as memory errors but also reveal how cultural symbols, narratives, and desires are processed, adapted, and sometimes transformed by the collective consciousness.

If I were Fruit of The Loom, I would add the cornucopia to the logo TODAY.

Conclusion

The tendency to simplify these collective memory lapses into a single, catchy term like “the Mandela Effect” is understandable in our fast-paced, information-saturated world. However, this oversimplification can lead to a pathologization (or at least a quasi-pathologization) of a fundamentally normal-ass human experience.

Furthermore, I think we should recognize these misrememberings as a form of collective creativity and public engagement. There is a dynamic relationship between official narratives and public perception, and I think this is potentially a way to hand-wave questions people might rightfully have. This makes me hesitant to use the term “Mandela Effect.”

All of your possible explanations could very well be the case by going with Occam's Razor.

But at some point that doesn't work anymore. Things, ICONIC things have changed. Its like as if your own name, or that of someone close has changed.

No rebranding of stuff, not any faulty things from the brain.

Things of our past have have changed, period. And there are flip flops. With the latter there's a big focus on things that changed, before they changed back. There's just too much personal proofs. Of course I say personal, as it's not something that to be put away somewhere in the science world yet. This besides the fact that for one something has changed while for another person the same thing hasn't changed. And it's obvious when you are to close to the change, having it even more ingrained in the brain than needed to be 100% sure of a change having happened. It's very likely when you are to close, you memory changes along with the change of a subject. This is why we don't have an all out freak out in the world. This is obvious, because most Brits don't know their flag has changed. And of course of all kinds of companies, not having their workers come out in droves that their brand has changed in some way.

"Science" throws money to invent new stuff, without any limits by for example rules what NOT to do. Just like AI, being more and more advanced, without any brakes to it's advancement. And there's competition to this, which makes almost impossible stop AI getting more and more advanced. And no AI doesn't need to be self-aware to be dangerous. Program it for death is all that's needed.