The JK Rowling Effect

Cancel Culture’s Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Getting The Monster You Asked For

Culture war’s worst villains don’t start that way. We are born into a world in motion; our beliefs, instincts, and errors form in relation to the conditions around us. No one emerges fully formed with a manifesto. But under the right conditions—outrage, shame, public exile—people don’t just reveal who they are. They become something new.

Cancel Culture doesn’t just expose villains—it manufactures them. This is what I call The JK Rowling Effect: someone says or does something off-color—maybe likes the wrong tweet—and the response treats it as final. Apologies are refused. The person becomes a symbol and thus an image-commodity. The person may repent, but it is rebuked by a mob which is consuming the experience of rebuking them, which can not be experienced if the person isn’t a villain.

People still make choices. But the menu shrinks with every denunciation. And by the end, we’re no longer arguing with someone who liked a weird tweet—we’re arguing with someone who just released a song called Heil Hitler.

Liking Tweets

We hear a lot about JK Rowling’s anti-trans views, but the mainstream narrative borderline ignores their origin. In 2018, J.K. Rowling liked a tweet calling out “men in dresses.” It wasn’t her tweet. It wasn’t a statement. It was a like—an ambiguous, low-effort gesture that might’ve meant agreement, curiosity, wanting to come back to the post later, or a mistake made while scrolling carelessly.

This sparked a huge amount of backlash, including media headlines, denunciations, fan outrage, and social media mobs. What happened next wasn’t her being convinced to do better—it was her being cornered into a public identity.

Rowling's spokesperson stated that the like was accidental, calling it a “clumsy and middle-aged moment.” Rowling herself explained that she had intended to screenshot the tweet for research purposes, as she was taking an interest in gender identity and matters (as any “young adult” author is incentivized to do).

The attempt to smooth things over didn’t matter; she was branded a transphobe. Not “questioning,” not “unclear,” not “in need of dialogue”—a villain. Articles were written. Twitter lit up. A line had been crossed, and for many, the verdict was already in.

Over the next year, Rowling doubled down—not by issuing a manifesto, but by defending Maya Forstater, a British researcher whose contract was not renewed after she posted a series of gender-critical statements. Rowling’s tweet:

“Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like… But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real?”

This was the real turning point into transformation from beloved author to ideological combatant. Each escalation from critics was met with a harder response from her. By 2020, she published a lengthy essay defending her stance, positioning herself as a “feminist concerned about the erosion of sex-based rights.” It was thoughtful in parts, incendiary in others, but above all—it was final. She had embraced the role.

This is the JK Rowling Effect. A person or group expresses a controversial, ambiguous, misinterpreted, or even plainly wrong view, and instead of being engaged, they’re fully defined by and attacked for it. The response is moral absolutism: the person is cast as a villain, and that treatment pressures them toward adopting the very identity or ideology they were accused of. The social performance of condemnation doesn’t neutralize harm; it accelerates it, manufactures it, and turns a possibility into a certainty.

The Mechanics

The JK Rowling Effect is a pattern—repeating, predictable, and scalable. It happened to many long before Rowling; it happens to celebrities, politicians, content creators, activists, and anonymous nobodies in a group chat. What ties the cases together is the sequence: ambiguity becomes identity, identity becomes target, and the target becomes real.

It is a five-stage process:

The Offense (Real, Misread, or Exploratory)

Someone says something that lands offside. Maybe it’s genuinely offensive. Maybe it’s phrased poorly. Maybe it’s just a question. The internet doesn’t care. Nuance doesn’t go viral. Conflict does.

The Verdict Is Instant

The person is declared guilty—not of curiosity, but of ideology. There is no distinction between wondering about something, being misquoted, or being a bigot. The mob—and often the media—collapses all three into one category: Bad Person.

Repentance Is Not Accepted

If the person apologizes, it’s dissected. If they clarify, it’s seen as evasive. If they stay silent, it’s taken as proof of guilt. The only acceptable performance is groveling—and even that often fails. The person becomes stuck in a social position they can’t get out of, no matter what they do.

Alienation and Reidentification

At this point, a shift happens. The person loses their previous social identity—fans, colleagues, allies drop them—and they begin to find validation elsewhere. Often, it’s from communities that actually do hold the views they were originally accused of. But now, those views come with comfort, belonging, and the feeling of being seen.

Embrace of the Role

Eventually, the person accepts the identity they were cast into—not because they always believed it, but because it’s the only identity left available. They go from vague gesture to full-blown ideology. Not always as a matter of belief. Sometimes as a matter of survival.

This process is the result of a social economy built on incentivized outrage and spectacle. Every step of the JK Rowling Effect generates content: quote-tweets, takedowns, reaction videos, articles, apologies, counter-apologies, explainers, thinkpieces. Everyone on every side gets a turn performing their moral clarity.

And that performance necessitates villains. For the progressive side, JK Rowling is to be battled.

The condemnation creates a rush of righteousness, a sense of superiority, and a temporary clarity. But it only works if the object of condemnation feels deserved. If there’s room for doubt, the performance weakens. So complexity gets stripped away. Context becomes threat. The person on the other end can not just be wrong—they must be evil.

This is especially potent within fandom cultures, where identity is cultivated through alignment with media, creators, ideologies, and each other. These commodified communities operate competitively—belonging is earned by taking the right positions loudly and visibly. For Rowling’s LGBTQ+ fans especially, the “Harry Potter universe” wasn’t just entertainment. It was a safe space, and Rowling’s perceived betrayal of that space became a betrayal of profilicit self. To remain in good standing, fans had to choose: her, or themselves.

Influencers within those ecosystems have even stronger incentives. Changing your mind alienates your audience. Nuance threatens your brand. And if your brand is built around visibility in a moral fandom (veganism, feminism, LGBTQ+ are fandoms, I’m sorry to report), forgiveness becomes financially disincentivized.

This is explicitly a large part of why I do not even attempt to make my analytic content into a job. Would I be mad to make a bunch of money for saying what I think? No. But to pursue that is to pursue incentivized thinking (this isn’t entirely possible to avoid, but it is possible not to pursue).

Meanwhile, the person being cast out—Rowling, in this case—is stripped of access to “general” public space. She’s no longer neutral; she’s radioactive. Mainstream fans with progressive leanings abandon her. Moderate coverage vanishes. And the only remaining audience willing to embrace her is the very crowd she was accused of aligning with in the first place.

At that point, a new fan relationship forms—one based not on her writing, but on her resistance. She is now financially and emotionally incentivized to perform for them. The backlash doesn’t just exile her. It delivers her to the reactionaries, who are all too eager to give her a home, a cause, and a cashflow.

(It needs to be said this is not exclusive to one side of the political spectrum. Many of the people Rowling fights with are also subject to this exact same dynamic; what I term “Yes, But It’s Good” Leftism is a clear example of the JK Rowling Effect.)

Platforms don’t intervene. They amplify. The algorithm knows that escalation keeps people engaged, and radicalization is more addictive than dialogue. At scale, moral condemnation becomes content. Keeping the show going is profitable, fixing the problem is not.

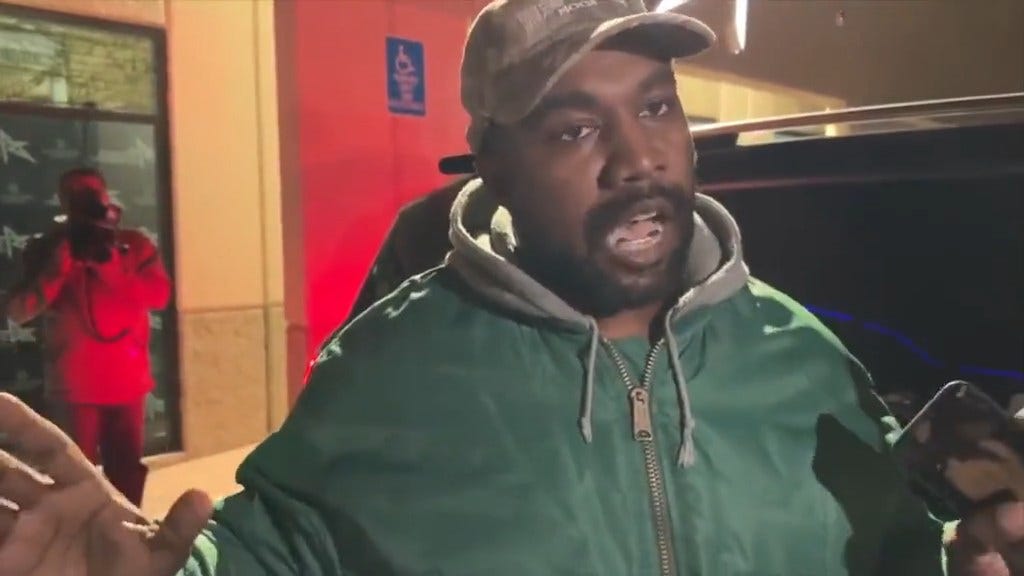

Kanye West as Case Study

If J.K. Rowling was cast as a villain and eventually accepted the role, Kanye West has taken it a step further.

His song Heil Hitler isn’t subtle. The title alone is designed to offend. But the lyrics are more than just shock value—they’re a twisted articulation of what it means to be cast out, stripped of grace, and locked into a narrative you didn’t write. This isn’t an ideological manifesto—it’s retaliation. And he tells you that himself.

“So I became a Nazi / yeah bitch, I’m the villain.”

That’s the thesis. Not “I’ve always been this.” Not “this is what I believe.” It’s “you decided I was a monster, so fuck it, I’m a monster, and fuck you.”

Let’s look at what leads up to that line. The song opens in pain and grievance:

“Man, these people took my kids from me / then they froze my bank account”

“I got so much anger in me / got no way to take it out”

Kanye sets the emotional context early: loss of control, loss of family, financial ruin. That’s the core wound—not politics, not Hitler, not ideology.

To be clear, when Kanye says “these people,” he is referring to Jewish people. And he does actually demonstrate anti-semitism (just as Rowling is, at this point, vehemently anti-trans). It’s important not to miss this, but it’s not the point. The point is lashing out.

He moves from grief into psychological fragmentation:

“Think I’m stuck in the Matrix / where the fuck’s my nitrous?”

It’s dissociation, paranoia, and posturing. The tone shifts fast—before long, he’s diving into crass self-degradation:

“Yes, I am a cuck / I like when people fuck on my bitch”

This isn’t a sincere confession. He’s working to beat others to the punch—humiliate yourself before anyone else can do it for you. It’s an act of strategic shame, a twisted flex. He isn’t saying “I’m weak.” He’s saying, “Try hurting me—I already did it better.”

“The shit I’m posting on Twitter / they telling me ‘Ye, don’t say that’”

Here, he brings it back to public image. He's being warned, censored, silenced. Then the line that centers the whole track:

“[They] see my Twitter, but they don’t see how I’m feelin’ / So I became a Nazi / yeah bitch, I’m the villain.”

This is not a political declaration. This is revenge theater; the JK Rowling Effect sung in first person. He doesn't claim to have always held fascist beliefs. He doesn’t explain or defend anything. He frames the transformation as a reaction. He became what the mob told him he was. Not because it’s true—but because there’s power in owning the insult when you’re not allowed to be anything else.

From there, the chorus loops endlessly:

“[N-word] heil Hitler / all my [N-words] Nazis / [N-word] heil Hitler”

The repetition is numbing. It’s not about meaning—it’s about saturation. He turns the phrase into something that has no room for interpretation. No subtext. No escape.

In between, we get image flashes:

“She wanna fuck in Japan / I put the chrome on the Benz”

“She reaching down in my pants / she got the world in her hands”

These aren’t just brags—they’re set design for the villain role: wealth, sex, danger, transgression. He’s not interested in coherence. He’s constructing an image: unrepentant, obscene, above shame.

And that’s what makes this track such a pure case of the JK Rowling Effect.

Kanye doesn’t sound like a man converted by ideology. He sounds like a man cornered by public condemnation and choosing to punch his way out by becoming the exact thing he’s accused of. Not because he believes it. But because, in his eyes, that’s all that’s left.

It’s not sincere, per se. It’s worse.

Regardless, this song is being integrated into the public consciousness. I see people calling it “catchy” and I don’t quite get it (IMO, Kanye is a tremendous talent and this is low-effort crap by his standards). Obviously taste is subjective, but all I hear is a very mentally ill man mad at how he is been treated.

Make no mistake, I feel very bad for him, and I don’t mean some kind of performative pity. If my kids were taken from me, I would be a rabid dog. I also sympathize with how he feels about the endless bad-faith attacks on him. I have been through similar. At one point, before he did rear into full-on anti-semitism, a conversation between he and I likely could have been good for both of us. It likely wouldn’t be now.

He is not just performing the JK Rowling Effect. He didn’t start as an anti-semite, and he is now, no matter what degree of irony it’s layered in. Even so, many are resonating with this song for completely non-bigoted reasons. Many are edgelords with various social grievances, some valid some not. Some probably have bad beliefs. Some probably have good beliefs.

To me, someone who abhors Hitler and anti-semitism, I’m not even offended by the song. I can see what it is: it’s “rebellion.” It’s doing what you’re not supposed to. People do that for a reason, and in a lot of ways, that reason is the JK Rowling Effect. Many of our villains, real and pretend, become villains due to a chip on their shoulder—a genuine slight that burrows deep and becomes a resentment.

Conclusion

When commodification, social punishment, and unresolved resentment collide, it’s not just a cultural glitch or personal failure. It’s a system. It’s social production.

The JK Rowling effect is when commodification and market incentive interface with the lack of ability to deal with that resentment in a manner which moves toward its nullification. This is, of course, cyclical. There is market incentive to keep people from developing the very capacity that would dissolve the conflict—and without the conflict, there’s no content.

At its core, it’s a process of villain creation—a cycle in which ambiguity or dissent is collapsed into identity, and that identity is punished so thoroughly that it becomes the only thing left to cling to. People are cast out, branded irredeemable, and then expected to quietly disappear. But they don’t. They harden. They reorganize. And eventually, they perform the role they were given—because there’s no path back, and because the system rewards the spectacle.

This process feeds itself. Public shame produces content. Conflict fuels platforms. Identity-based outrage becomes marketable inventory. And any possibility of genuine dialogue—of tension being metabolized instead of monetized—is structurally suppressed.

People still make choices. Rowling made hers. Kanye made his. But the conditions under which they made those choices were shaped by an ecosystem designed to trap people in their worst moments and reward them for doubling down.

People do not start as villains; there is a system in place that makes villainy the most feasible path to survival.

Very touching, and casting a painful light on this painful tragedy. I almost feel sorry for Rowling and Kanye. And I ache for all the lesser-known people who have entered their "villain era" in similar ways, without anyone named Peter or Coffin or anything else to write up a post mortem of their fall from grace, or perhaps neutrality. No one with anyone to care enough for them to read about what they may have gone through. As you mentioned in the Discord server, there are worrying signs pointing to Pedro Pascal being put on a massive pedestal by the media for the purpose of showing him fall, so maybe he's next! I really hope not, but I fear the worst in this climate

Side note - It's more correct to write simply "antisemitism", more than "anti-semitism". There is no such thing as "semitism". There are people who can be referred to as Semitic, Jews by the traditional definition but that could be extended to most other speakers of Semitic languages, including many people who may be known as Arabs, and many others from west Asia and northern Africa. But "anti-semitism" implies the existence of "semitism", which does no exist