Stop trying to make "Unhoused" happen

"You ain't cool unless you pee your pants" but for homelessness

In recent years, homelessness has become worse. Homelessness in the United States has increased by about 6% yearly since 2017. In 2022, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) counted around 582,000 Americans experiencing homelessness. This is about 18 per 10,000 people in the US, up about 2,000 people from 2020.

So, how should we advocate for the homeless? Should we demand that homeless people’s situation be alleviated? Should we demand institutions that attend to homeless people’s needs and shelter them? Should we pressure those institutions to create programs providing access to previously inaccessible knowledge and skills to homeless people?

No! Why would we focus on materially improving homeless peoples’ conditions when we can focus on language!? Of course, The Guardian, a shining beacon of progressivism, can distinguish what is truly important about an issue—and has done just that with their new article, “Is it OK to use the word ‘homeless’ – or should you say ‘unhoused’?”

Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up.

“Unhoused” is an excellent example of the capitalist structure attempting to dictate languageThe post that sparked this conversation was right: people are exhausted, isolated, and locked out of community. But the way we frame that condition matters. By calling these spaces “third,” Oldenburg unintentionally ranked them beneath home and work, and we absorbed that hierarchy. By mostly describing bourgeois venues, he made them sound like privileges granted under certain conditions, not fundamental needs. And now, with the concept in the hands of a publisher, they’ve become something managed and administered—an idea you subscribe to, rather than a reality you live.

That arc tells us something about more than “third places.” It shows how community itself has been treated: first tolerated as a luxury, then hollowed out, and finally commodified. The irony is that the very word meant to highlight its importance ended up preparing it for capture.

If we want to rebuild community life, we can’t keep agreeing it belongs in third place. It has to be first—the foundation of everything else. Otherwise, we’ll keep watching as the spaces where life actually happens are either stripped away or sold back to us as intellectual property.“trying to make fetch happen”—for the sake of distraction.

Pedantry

Why “unhoused?” The Guardian introduces us to a cast of characters to tell us.

Elizabeth Bowen, a professor of social work at the University of Buffalo, explains it as an effort to humanize people. “It's a powerful way to remind us that the issue is really a housing problem,” she tells us. “There can be a tendency to think about homelessness in more individualistic ways, like it’s a person’s personal failing or the result of their life choices. When really the most important thing is that we just don’t have enough affordable housing in this country.”

Firstly, I love that she can’t avoid saying “homelessness” as she explains why not to say “homeless.” But more importantly, a lack of affordable housing isn’t the problem (we’ll deal with that in the next section).

Beverly Graham, director of a non-profit (because of course she fucking is), was sitting in an executive leadership class (because of course she fucking was) in Seattle (because of course it fucking was) in 2006 when she says she first recalls using the word “unhoused”:

Graham hadn’t planned on speaking up. But her classmates – two dozen regional business leaders – were discussing the number of homeless people in the area, and their perspective felt very different from the one she had gained after years of helping vulnerable Seattleites. She had to pipe up.

“I said, ‘They’re unhoused,’” remembered Graham. “They have a home: Seattle is their home.” OSL has used the word ever since to describe people lacking a fixed abode, feeling that “homeless” had gained discriminatory, ugly connotations.

- “Is it OK to use the word ‘homeless’ – or should you say ‘unhoused’?”

I think it’s most important to note that the article tells us when she first used the term rather than when she first heard it. Next time I see a homeless person in, let’s say, Seattle, want to know what I’m not going to do? Ask them, “Excuse me, sir, is Seattle your home?”

Graham most likely didn’t get the term from a homeless person. And if she did, it was most likely from a person who maintains a gratitude policy, as in “this city is my home, and I am thankful for my blessings.” If one were to ask this hypothetical person, “Would you like a home?” their answer would likely not be, “No thanks. Seattle is my home.”

The Guardian also introduces us to Mark Horvath, founder of Invisible People and former homeless person, who highlights that “most homeless people still say ‘homeless.’” Imagine that! Those who are experiencing homelessness aren’t hung up on semantics! They’re concerned with getting through the day, finding their next meal, and seeking shelter from the elements.

However, Horvath is buried in the middle of the text, and I believe is only included to legitimize the idea that this article is “neutral.” We can see how this is employed in the article’s conclusion, which reveals a subtle yet clear bias. While it nods to multiple perspectives, it unmistakably champions the shift from “homeless” to “unhoused” as a pivotal move in reshaping the discourse on homelessness. Here’s the final line:

It’s not nearly enough, but the term “unhoused” – giving a fresh name to a tired, infuriating topic – is one small strike in that battle over public opinion.

The author suggests that the issue of homelessness has become stagnant or repetitive in public discourse. Changing the term to “unhoused” is thus presented as a rejuvenating approach, seemingly infusing new life into what is also characterized as a “battle over public opinion.” Using dramatic terms like “strike” and “battle” suggests that this isn't a mere discussion but a vital fight to control the narrative around homelessness, which must be the problem.

Bowen says, “we just don’t have enough affordable housing in this country;” Graham provides us with a cultural explanation and pitches us the cure.

This is simply viewing the situation as a marketer would (not a shocking turn with the market fetish our society is trained to have). It’s not the problem, though.

The narrative around homelessness has changed significantly during my lifetime. From its portrayal in the 1980s as a result of personal failings or choices (with terms like “bums,” “hobos,” and “vagrants”), people generally talk about it today in a manner that, to varying extents, underscores systemic and socio-economic challenges, such as income inequality and lack of affordable housing. There is also much more talk about mental health and addiction and pushing for a reduction in policies criminalizing homelessness.

“Exponential Growth”

However, this idea that the labels must be changed doesn’t even grant that the perception of homelessness has gotten any better, and if it has, it isn’t happening fast enough, necessitating a linguistic change! Further, we’re meant to believe this is a report on a current change in American language, but it isn’t.

This is paradoxical; if it were happening, people would already understand the necessity of changing the language (because it would have already happened a lot), thus nullifying the need to convince anyone of it. But it must be happening if no one needs to be persuaded of it!

Again, it isn’t!

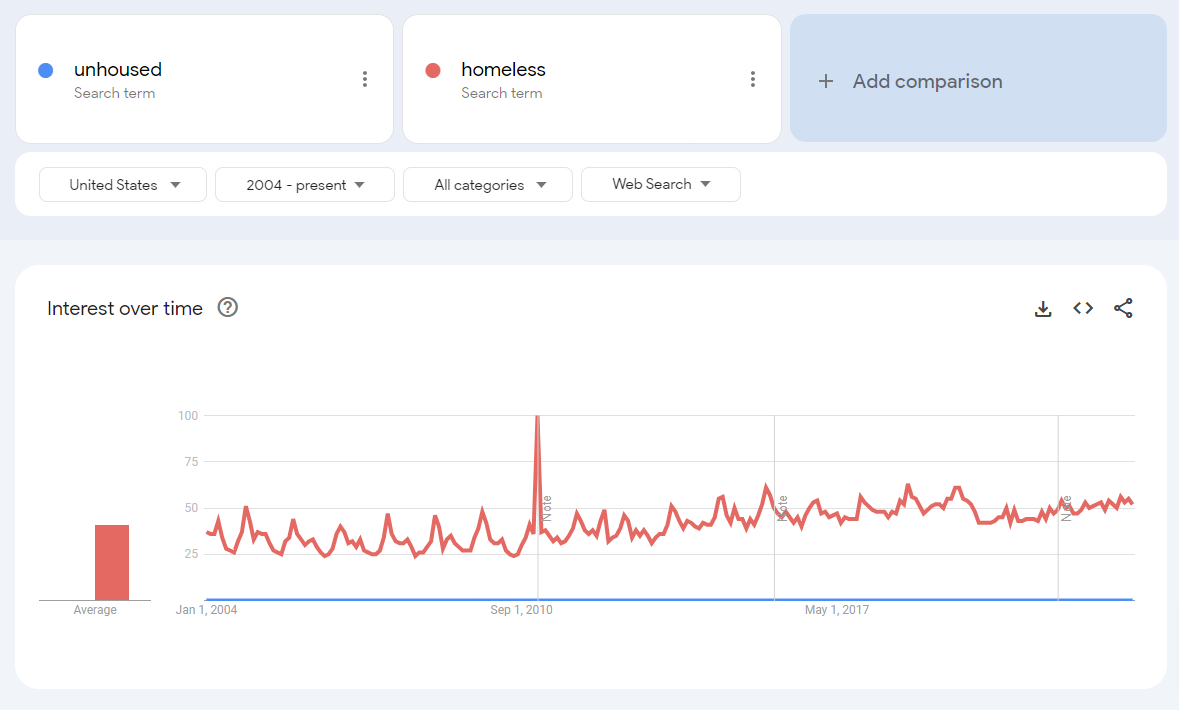

The claim that “the use of the term ‘unhoused’ has grown exponentially in the last few years” is supported by mentioning both the NOW Corpus and Google Trends. However, it neither shows nor links to specific data, so I figured I would do my own comparisons using the source I am most familiar with, Google Trends. First, I compared “unhoused” with “homeless,” where the use of the former cannot even be seen relative to the use of the latter:

So, to handicap it a bit, I ran the same comparison with “homelessness,” where we can see some growth in “unhoused” use:

The author mentions a tweet as the “first usage of the term on twitter,” however, the linked tweet is just a post of a local news headline that used the word. Then, we’re given a historical use in Shakespeare, as if his totally unrelated use of the word somehow legitimizes this contemporary one.

As I said in the introduction, it’s “trying to make fetch happen.” But we also must view “fetch” through the lens of “you ain’t cool unless you pee your pants”; an authority deceptively dictating what is “cool.” Further, in this case, “cool” is a pledge of fealty to the neoliberal concept of “social justice,” an entirely idealist, utopian prospect that the capitalist class keeps well-funded to avoid progress when possible.

If it was so cool, why don’t we see more people peeing their pants? If people were saying “fetch,” how come I’m not hearing it?

This dance around terminology and the optics of compassion might give some the satisfaction of appearing “woke,” as well as giving them something to claim their neighbor is bad about (“he says ‘homeless’ so he’s the bad guy and I know better so I am the good guy”) without really engaging with the underlying systemic issues of homelessness.

But it is as cool as peeing one’s pants.

Affordable Housing

Though it is the ultimate goal, the claim isn’t just “we should focus on terminology,” it’s “this terminology urges us to focus on advocacy for more affordable housing.”

The call for “more affordable housing” might, at first glance, seem aligned with a Marxist critique. However, deeper scrutiny reveals significant points of contention between the two perspectives.

Affordable housing initiatives can offer immediate, short-term solutions within the capitalist framework. However, Marxists attribute homelessness to capitalism. In capitalist societies, housing is a commodity for profit (or control) rather than a public good.

In Capital Vol. 1, Marx discusses the commodity form. In this context, a house transitions from primarily offering shelter and security to being a means of extracting value (or reproducing capitalism in some other way). Thus, people's needs are not the motive for constructing or opening new housing. Housing isn’t seen as necessary infrastructure—and that’s precisely what it is.

Despite its stated intentions, affordable housing remains entrenched in this commodity-driven system. Many affordable housing initiatives rely on public-private partnerships, tax incentives, or other market-driven strategies to entice private developers to build or maintain lower-cost units. Often, this means creating opportunities to build luxury apartments with a small percentage of “affordable” units, ultimately driving land values up and, thus, the cost of living in any given area. While someone’s rent might be decent in such a complex, that person’s local grocery store might be Whole Foods, which is impractical for someone on a low income to shop at.

The “affordable” units might only need to remain affordable for a limited time, too, eventually taking them out of poorer people’s reach. These are a few examples I can come up with quickly, but we shouldn’t limit it to what I, a non-lawyer with no driving incentives, can conceive of. The devil is in the details.

In contrast, the Marxist view calls for the complete de-commodification of housing. Moreover, while initiatives like rent subsidies might offer brief reprieves, Marxist solutions advocate broader changes in the relationships of power, addressing intertwined capitalist issues such as wage suppression and wealth inequality.

For instance, China’s approach might sound similar to an “affordable housing” program, but it also maintains state control over the market. At any time, the proletarian-owned state can dictate terms requiring access, construction, and other changes without incentivizing capital. China has a homeownership rate of 90% (compared to the US’s 65.9%). While China isn't without its challenges or flaws, it at least has mechanisms to ensure its citizens' housing and an economic program aimed at ordinary people’s prosperity.

(Side note: it was challenging to find fair resources detailing China’s policies on homelessness, with many “sources” claiming the state is taking homeless people off the street and “hiding” them… which, I mean, think about it. Is that not sheltering them? Hiding them from American eyeballs is also hiding them from the elements. I am not saying this is definitely spin, but it’s what crossed my mind.)

Capitalism, by design, appropriates wealth to those who own the means of production (and reproduction) of capital, creating a ridiculous mathematical problem that eventually leads to a value crisis. As this occurs, a dual reality emerges in which properties remain vacant as investment assets, while a portion of the population struggles for basic housing.

And what about once a person has a home? Are they able to work? Are they able to provide for themselves? If not, why? A lack of skills or knowledge? Mental health issues? Will they be able to maintain a home without any of this? What can be done about this?

While affordable housing initiatives in capitalist systems may offer band-aid solutions, the crux of the problem – the commodification of essential needs – remains unaddressed. If the aim is to solve the housing crisis, the debate should shift from mere affordability to rethinking the foundation of our economy, starting with these apparent contradictions.

Conclusion

In addressing the growing homelessness crisis in America, it's imperative to focus on the root causes and systemic issues rather than being sidetracked by semantics.

Language and representation are not the drivers of these issues; at most, they are reflections. They cannot replace substantive action and transformation of our current economic system. The debate around the term “unhoused” vs. “homeless” spotlights how society is directed to fixate on superficialities while neglecting the foundational problems that create and exacerbate homelessness.

The call for "affordable housing" provides only temporary relief—and only for some. What does it do for people who can not afford a sandwich? Why are there people who can’t afford a sandwich? Material contradictions are at the center of these problems that can be resolved, but it will not be done by saying something different. It will be through class struggle.

Ultimately, if we genuinely want to address the issue of homelessness, linguistic debates are idiotic distractions. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up.

Hey Peter, long time follower first time commenter.

I've noticed in several recent posts you made and also your most recent documentary (interesting watch) that you seem to think of modern China as an example of a communist/socialist society that others could aspire to. I think, however, that we should be careful before we look to China as an example to follow for most purposes. I don't know where you get your information about the country, but you should be aware they like to play fast and loose with the truth in their promotional material and propaganda.

I've been following some people who lived there for a long time and watched the changes unfold as Xi Jinping took over, and what they share seems to be plenty of cause for caution. You might say that's a biased source, but even random economics channels I follow are saying similar things to what they recently said, for example that China has been hiding more and more economic indicators. Why would they hide things that might be good news for them?

The guys I follow have a weekly podcast where they discuss various issues and a clips channel where they take bite-sized fragments from the podcast (and a few other channels). For example, to get back to the post's topic, there's one (https://youtu.be/oLMnVpuhGD0) where they explain how homeless people are actually just shipped off into the countryside so they can't come back. They may be sheltered in a bus for a couple of hours that way, but I think you'll agree that's taking a bit too much liberty with the idea of providing shelter.

Another clip that comes to mind is one where they explore the case of the vlogger who got silenced for vlogging about the pathetic pension an old lady gets from the "socialist-with-Chinese-characteristics" state and his attempt to buy her a decent meal with it (and ending up using his own money too; https://youtu.be/bI_qmHook7c).

You probably wouldn't find things like that if you look for them since they embarrass the government and thus are quickly erased. That's why it's nice to have people like that who can keep an eye on things that will quickly be erased.

You don't have to believe me, but if you even look at how their diplomats and officials behave on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, not to mention how the various channels and personalities that promote the Chinese government's talking points have an interesting tendency to all use the exact same stories and even wording even when they claim to be independent, you hopefully agree that taking at face value the media that is their mouth piece (e.g. Global Times, China Daily) isn't worth much either.

One other source I'd mention is the Great Translation Movement (https://twitter.com/TGTM_Official), where Chinese speakers translate various things taken from the Chinese internet to penetrate the language barrier to show the contrast between how the government portrays itself toward the outside world, what they publish for the foreign audience, and what they feed the domestic audience, not to mention what people think of various other places like Japan, Korea or the US. Note too that as mentioned above, if the government finds something to dislike, it will quickly make it disappear, so it's tempting to think those things are implicitly condoned.

I agree with most of what you say, including your message at the end of your recent documentary, but let's be careful what we believe about a country that is getting more and more opaque.