Pro-AI, But Also Reactionary

The discourse around AI art is overwhelmingly shaped by reaction. On one side, anti-AI voices claim it is “theft” and “not real art,” repeating tired intellectual property tropes that ultimately serve corporate power. I’ve written about this many times, but they keep coming up with new angles to dissect.

On the other side, though, even some of AI’s defenders are defending it in ways that are just as reactionary, bludgeoning artists and dismissing the value of cultural labor altogether.

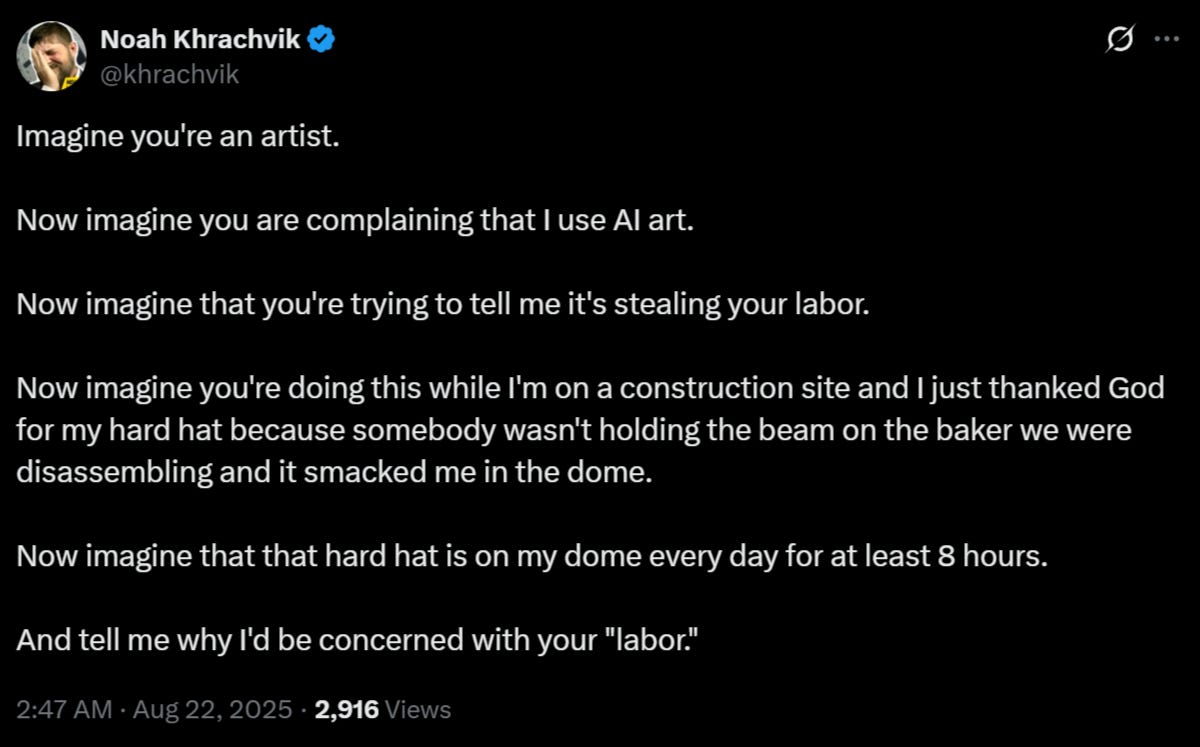

Recently, Noah Khrachvik (an Executive Board member of the American Communist Party, one of many fandoms masquerading as organizations or political parties) posted a tweet that captures this tendency perfectly:

Imagine you're an artist.

︀︀︀︀Now imagine you are complaining that I use AI art.

︀︀︀︀Now imagine that you're trying to tell me it's stealing your labor.

︀︀︀︀Now imagine you're doing this while I'm on a construction site and I just thanked God for my hard hat because somebody wasn't holding the beam on the baker we were disassembling and it smacked me in the dome.

︀︀︀︀Now imagine that that hard hat is on my dome every day for at least 8 hours.

︀︀︀︀And tell me why I'd be concerned with your "labor."

- Noah Khrachvik (X)

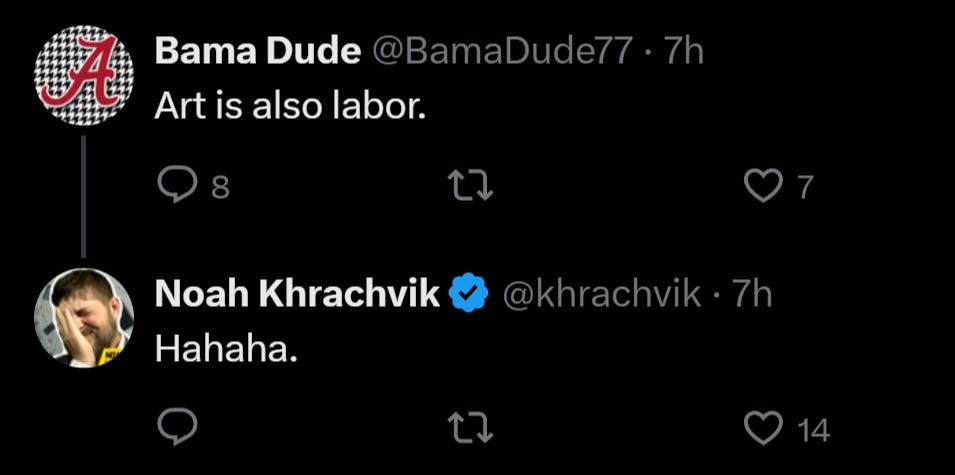

When someone replied, “Art is also labor,” Khrachvik responded simply: “Hahaha.”

On the surface, this might look like a defense of AI, and in the most literal sense, it is. However, the actual logic here is reactionary (just not in the anti-tech way typical AI conversations go).

Firstly, Khrachvik cuntily pits one form of labor against another, as if physical, dangerous work is “real,” while artistic work is frivolous. This logic mirrors the identity politics that the ACP claims to be against. The twist is that, instead of identity, the lines drawn relate to different jobs—though we could discuss it as a sort of identity politics, as often jobs equate to identity in our current social context. Regardless, the effect is the same: it divides workers against each other, invalidates the struggles of one group, and trades solidarity for competition.

This dismissal of cultural and intellectual labor isn’t new. We saw the same posture in 2022’s Starbucks Barista Discourse™, when Haz Al-Din (also on ACP’s executive board) argued that Starbucks workers weren’t truly proletarian because their tasks were “unproductive.”

But Marx himself was clear:

“The determinate material form of the labour, and therefore of its product, in itself has nothing to do with this distinction between productive and unproductive labour. For example, the cooks and waiters in a public hotel are productive labourers, in so far as their labour is transformed into capital for the proprietor of the hotel.”

He even extended this logic to performers:

“An actor, for example, or even a clown, according to this definition, is a productive labourer if he works in the service of a capitalist (an entrepreneur) to whom he returns more labour than he receives from him in the form of wages; while a jobbing tailor who comes to the capitalist’s house and patches his trousers for him, producing a mere use-value for him, is an unproductive labourer. The former’s labour is exchanged with capital, the latter’s with revenue. The former’s labour produces a surplus-value; in the latter’s, revenue is consumed.”

Marx’s point is straightforward: what matters is whether labour is consumed by capital and produces surplus value, not whether it looks like “real work” or not.

By that standard, baristas (and artists, writers, musicians, and programmers alike) are productive workers. They aren’t automatically productive workers, but neither is anyone. A handiman working alone fixing your sink for $50 is not producing surplus value for capital, while the same handiman is doing so when working for a company (either as a traditional employee or in the gig economy; an Uber driver is a productive laborer as the ride is not simply a ride, it is an Uber).

The thing that matters in the “productive or unproductive labor” conversation isn’t the task being accomplished, but what the task’s relation to capital is.

When Haz claimed the barista wasn’t really working, I wrote at the time (ironically, published initially on Midwestern Marx, Khrachvik’s pre-ACP endeavor) that the coffee was more or less a souvenir of what was actually being sold: a transaction structured around spectacle and ritual—the performance of the barista. Either way, the barista is engaging in productive labor as a Starbucks employee.

Khrachvik’s mockery of “art as labor” is just the same mistake with new scenery. Both take aim at work that is visibly mediated (service, culture, performance) and dismiss it as fake. However, most art produced by creative workers is for capital in one way or another.

These are precisely the moments where capital exploits labor: the service, the song, the performance, the poured latte, even the edited video. To laugh them off as “not real” is to fall back into the bourgeois fantasy that such work is frivolous, ornamental, or parasitic. In reality, cultural and service labor is precarious, underpaid, and tightly policed by gatekeepers who work to minimize cost, which is why capital is so eager to delegitimize it.

Ironically, this leads to the same framework the IP fetishists rely on: art as property rather than labor. The anti-AI crowd clings to this framework when they call training “theft,” defending artists by characterizing them ultimately as content landlords. Khrachvik falls into the same trap from the other direction: if art isn’t labor, then it’s only ever a hobby, ornament, or owned product. Both erase the reality that cultural work is labor exploited by capital. Both leave us stuck in the language of ownership, reinforcing the very system they claim to resist.

The “real labor vs. fake labor” conceit ultimately fractures solidarity. It pits various types of workers against one another as if one is “more real” or “more proletarian” than the other. Instead of recognizing the shared condition of exploitation under capital, it encourages us to rank forms of labor on a false hierarchy, which only deepens the divisions capital already exploits.

And once you say a form of work isn’t “real,” what’s left? If artistic or service labor isn’t labor, it must just be property; it is involved in exchange, after all. If this is the case, the artist must not be a worker and so must be a rights-holder, effectively a content landlord. This doesn’t protect them from exploitation; it just strips away the language of labor and solidarity.

In this way, both the anti-AI “theft” rhetoric and Khrachvik’s reaction end up reinforcing the same framework. They keep the conversation trapped on capitalist terrain, where art is always a question of ownership. Either you’re defending your “property” (anti-AI) or dismissing art as “unproductive,” but a circulation of value, and thus it must simply be some form of property (reactionary pro-AI).

In both cases, labor becomes invisible, and laborers remain divided.

I’m so grateful for your essays. The IP fetishism AI art elicits within the commercial art workplace is an exhausting argument trap. I feel a lot more confident in my beliefs and can spot reactionary behavior and avoid it.

How come these ACP guys don't know their Marx?