Cancelling the Cartoon Horse

Forget dead horses, it's all about imaginary ones now.

Bojack Horseman was a show about an alcoholic horse. Through its depiction of the main character, it had a lot to say about forgiveness and the drive to be a better person. It ended in January 2020, but this morning, as if to say, “Call me. My number ends in 4464 because I wanted an easy number to remember,” I logged in and noticed that Bojack Horseman was trending on X (lol).

Often, this means people are talking about different scenes or ideas – generally, it’s an interesting conversation when Bojack crops up. But today was different. Today, the attention was coming because someone had posted a clip from Bojack’s second, attention-seeking interview with Biscuits Braxby.

People’s response today was treating Bojack Horseman as a real Hollywood celebrity and canceling him.

I love the show, but that's not why this bothers me. I didn’t get mad when fictional people inside the show canceled Bojack; he's the type who actually should have been regarded as a shithead... until he wasn't. His character arc is that of attempting to understand what “good” is when one can not help being “bad” (partly by understanding what “bad” is and why), and the answers he eventually finds are ones most of us could learn from.

What bothers me is seeing people not only treating a fictional character as a real person but also pausing the narrative and ignoring the rest of the story.

Bojack Horseman is a work of advocacy for the adage “progress, not perfection.” The need to exert the faux-righteousness of cancel culture on a fictional horse from a show that’s been off the air for over three years as if he is real and that the narrative stopped where it was right to attack him shows us something we need to desperately get away from: the ideological impulse to attack imperfection at the cost of progress.

Biscuits

A clip of the scene in question was posted as a joke, the poster noting how monumentally Bojack chokes. A broken man endlessly seeking external validation, he can not resist returning to the well. It ends up being ruinous for him, as he not only does a lousy job dealing with scrutiny regarding his first interview but accidentally reveals information that paints him in a highly negative light.

The clip ends with Biscuits saying:

So to recap, you gave Sarah Lynn alcohol when she was a child. She then became an addict. When she was intoxicated, you had sex with her, and when she was sober, you gave her the heroin that killed her.

Then, in an effort to cover for yourself, you waited to call the paramedics

that might have saved her life. And you don't think you have any power over women?

This scene is mesmerizing, a turning point for Bojack that causes him to become hated and brings him to his true rock bottom. It mediates what happens when we don’t honestly deal with the issues in our lives, opting to “move on” rather than “work through.” Bojack stopped drinking but hadn’t entirely reckoned with the behavior, feelings, and expectations that “required” him to drink.

Bojack’s tackling of “cancel culture” is perhaps the most delicate work on the topic I have seen in any media. Season 5 laid most of the groundwork for it, but Season 6 puts it together.

The show demonstrates the divergence between media portrayal and a character's genuine essence, particularly with Bojack, who, despite his glaring imperfections, exhibits deep self-reflection and sincerity. This tension is also embodied in how the media’s portrayal is all the public knows of many things and the fickle way information is presented to influence us.

It doesn't shy away from highlighting the tangible repercussions of one's actions, as seen with Bojack, asserting that fame doesn’t put one above consequence. However, it repeatedly casts its critical eye on the media's role, showcasing how it can exaggerate, manipulate, or capitalize on celebrity. Characters like Hank Hippopotamus epitomize the dangerous power some stars wield, while others, such as BoJack, face intense scrutiny, sometimes even making it nearly impossible to do the right thing.

That isn’t to say Bojack is an example of a character who has repeatedly done the right thing at every turn. On that note, Bojack Horseman also wades into the contentious question of if individuals, once condemned, are capable of genuine transformation and, if so, whether society should offer forgiveness. What actions are forgivable?

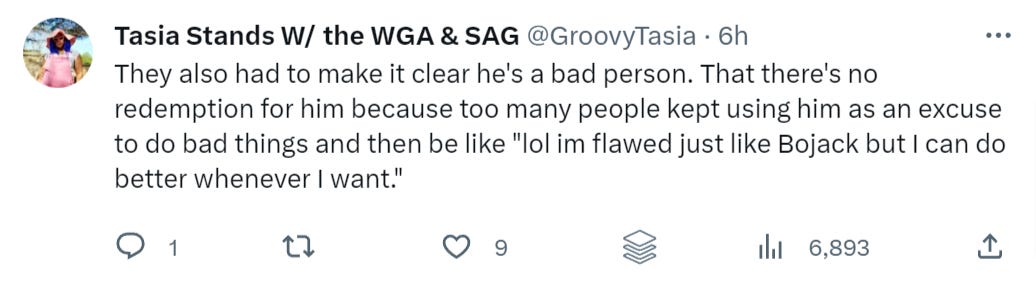

While the show takes a stance reminiscent of a 12-step program, if one were to take to Twitter/X, one would see the modern “cancel culture” answer of “None. Forgiveness doesn’t exist, nor should it.”

There are hundreds more posts like these, but the last one bothers me the most. The tone of this “backlash” is that people are not to be forgiven – people “are” their actions on an essential level – and this one cements that.

Perfection and Essentialism

Recently, I’ve written about a few different “viral” events involving regular American people displaying proto-class consciousness, which is, by definition, developing and imperfect. With Jessica McCabe, I showed that she was on the right track, and with Oliver Anthony, I did the same, with some criticism of how he characterized “fat people on welfare.”

Criticism that doesn't aim to destroy nurtures, but leftists weren't doing that. Sadly, people's ideological impulse is to attack imperfection. I’m writing about this canceling of a fictional horse to demonstrate the extent this ideology has taken root.

The demand for perfection is ultimately one of essentialism. In the team sports realm of contemporary politics and culture, one is either “good” or “bad.” If someone “bad” says something others agree with, those people are just “bad” too. If we asked, keyboard crusaders would deny that they think “badness” is an essential trait. But for them, it is.

As I lay out in my book Woke Ouroboros, idealism is the key to essentialism. One needs an answer to the question, “Why are they like that?” Without it, the group doesn’t make sense. These groups exist without a material distinction, so an ideal or superficial, non-fundamental trait must stand in for one. The ideal or trait becomes reified (treating or transforming an abstract concept or subject as/into a physical object or natural reality) as the “material” essence of the group.

Put another way, people seek explanations for why certain groups are what they are. However, many groups do not have a fundamental, material difference distinguishing them from the rest of society. Race, for instance, is not a fundamental difference but an ideology of difference based on superficial traits (though it can have biological, hereditary consequences on things like health outcomes).

So, people might lean on ideals, beliefs, or traits to define that group. Over time, they might become solidified in people's minds as the fundamental characteristics of that group. It's a way for people to categorize and make sense of the world, but it leads people to make oversimplified assumptions that are ultimately disconnected from reality.

Everyone, and every group, exists on a spectrum of experiences, beliefs, and traits.

The most significant danger of this essentialist demand for perfection lies in its ability to halt growth. By stamping a permanent label onto someone or something based on an isolated event or trait, we deny them the opportunity to evolve, learn, and change. In doing so, we also stifle our collective growth as a society.

We can see this effect most poignantly in the world of social media. One misstep, misguided comment, or a moment of ignorance can lead to a relentless barrage of criticism, often public shaming. While people should be responsible for their actions, it's equally important to approach mistakes with empathy, understanding the broader context, and providing opportunities for growth.

Additionally, essentialism and the pursuit of perfection overshadow the complex realities that underlie our beliefs and actions. For example, while race is an ideology with no inherent qualitative distinction, society's emphasis on racial differences has led to systemic discrimination, deeply rooted biases, stereotypes, and even different hereditary health outcomes.

What interests me about this Bojack Horseman incident is that it starkly portrays this essentialism; the show continues after the interview depicted in the clip. The narrative continues and addresses Bojack’s wrongdoing, and he does find redemption. It is bittersweet, but one can only have so much cake. The people posting about this do not care, though; the timeline of the show halts where they want it to so Bojack can be the person they want to attack rather than the one who does what is possible to set things right, even if that is a complex and not-entirely-possible prospect.

Whether it’s Bojack Horseman, a red-headed Southerner singing about politicians, or a suburban mother concerned her gainfully employed kids can’t get acceptable apartments, people on social media seem unable to see past what are ultimately temporary imperfections (and the fact that one of them is a fictional anthropomorphic horse) and instead want to cast them into the Basket of Deplorables, because, in their eyes, that’s all they’ll ever be.

Progress

The concept of “progress, not perfection” is not novel, yet it remains profound and relevant. Rather than rigid and unrealistic expectations of flawlessness, one can commit to continuous growth, even if slow. Bojack Horseman is a fantastic depiction of this maxim, underlining that growth is a journey filled with setbacks and learning moments. Further, by showing that it is worth it to try, Bojack ultimately does just that when it would be easier to throw everything away.

However, as shown by this cancelation of a fictional character, our current cultural climate shuns the ground between saint and sinner. The digital age seems to have amplified people’s cognitive biases, leading many to label and categorize swiftly, often without considering the entirety of a person’s journey or the broader context in which they operate.

Genuine growth – personal, societal, or even in a fictional narrative like Bojack's – is a process. It's not linear, nor is it consistently upward. It's marked by stumbles, U-turns, and the occasional fall. But what’s crucial is the intent to move forward, to learn from mistakes, and to become better versions of ourselves.

Bojack Horseman is a character who embodies the very struggle between progress and perfection, and this incident reveals a disturbing trend. It's as though many have forgotten the value of growth and redemption. Characters like Bojack are pivotal not because they represent an ideal to strive for but because they mirror the complicated nature of humanity. Their stories remind us that it is worth trying.

Unlike Bojack, I am responsible for no deaths (or the laundry list of… other stuff he was involved in). But if it is worth it for him to try, why shouldn’t it be for me?

This is why we see the obsessive need to perform perfection; society has swallowed a pill that says, “If we have flaws, it’s because we’re terrible people, and we should all hate ourselves. The best we can do is hide our evil from others and stop them from expressing theirs.”

Conclusion

The strange Bojack Horseman discourse I witnessed online underlines a deeper societal issue of essentialism and the ill-conceived ideology of perfection. Structures that create an impulse to judge, label, and dismiss are at the heart of this controversy. But by isolating individuals, characters, or even moments in time and holding them under an uncharitable magnifying glass, we deny them their nuanced histories and impede many from attaining dialectical understandings.

It's a stark reminder that we must prioritize progress over perfection, valuing the journey and lessons. Bojack's tale is not merely about an animated horse but a mirror reflecting our imperfections, the societal constraints we operate within, and the human potential for redemption. Rather than focusing on a static image of someone's past, we must encourage and celebrate the ongoing effort to change and improve as part of a fluid and changing world – while challenging societal structures that may hinder this progress.

The fight for a better world doesn't negate the need for individual growth. Yet, it's paradoxical that many who advocate for societal betterment by urging everyone to "#DoBetter" often doubt the capacity for personal growth and change. Collective and individual improvement are complementary, and their barriers often overlap.

While I am a Marxist and believe that people are beholden to the material conditions of society, I think we all want to do and live better. Ultimately, there is a lot in our way, but we don’t have to be.

You snapped on this one. Credit where credit is due.